Field Notes: Vietnam Training in Underwater Archaeology

Week 2 Wrap Up

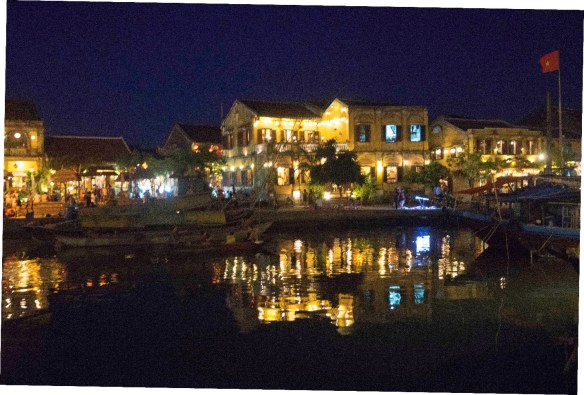

Field school life has settled into a busy but steady rhythm and the second week of training flew by! The trainees have been split into 4 teams and have been working on various projects under the guidance of their team leaders and supervision of the trainers. Some of these projects are under water while others are taking place around Hoi An.

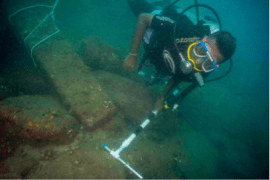

Underwater search and recording methods

The shallow, sheltered waters of Cu Lao Cham provide relatively safe training grounds for new divers; except for when curious tourist boats come a little too close to diving operations or the Vietnamese military schedules artillery target practice! Despite these disruptions, the teams have been steadily improving their underwater communication, search and recording skills in areas of high underwater cultural heritage potential that were identified during the previous field season. This week, teams re-located and recorded a stone anchor, possibly of Arabic origin, and nearby ceramic scatter in shallow water.

Ethnographic boat building

One way to better understand what we are searching for underwater, is to spend time with local boat builders to study the methods and materials that are used for constructing local vessels. This is also a great opportunity to get to know some of the locals and in doing so, learn more about local culture and possibly new sites to investigate. The teams spent time at various boat-building yards, recording interviews with the workers and the boats that were being built or repaired.

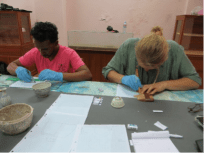

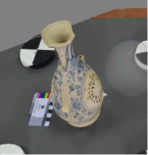

Shipwreck ceramics

As mentioned above, we have found some ceramics on the beach and in shallow waters around Cu Lao Cham. Some of these ceramics have been tentatively dated to about 3000 BP! Ceramics are an indicator of the type and level of trade that has taken place in the region and so it is important for us to be able to identify and record them in as much detail as possible. The Hoi An Centre for Cultural Heritage Management and Preservation has a collection of shipwreck ceramics from archaeological and salvage operations in Vietnam and we were given access to them to study. This gave me flashbacks of first year archaeology where I was horrified to learn that LICKING the artefact is one way to ascertain what type of ceramic it is! Luckily, such drastic measures were not necessary in this instance and instead, we spent time honing our drawing skills, describing the artefacts in a database and practicing the 3D photogrammetry that Ian has been teaching us.

Foreign traders in Hoi An

Hoi An was a major center for trade between the 16th and 19th centuries, attracting traders from India, China, Japan, Portugal, England, Holland and more. The built environment of the Ancient Town bears testament to this period, as do the tombs of the foreign traders that can be found on the outskirts of town. We were tasked with locating and recording some of these tombs; a task that was easier said than done for some teams! We spent a rather hot morning trooping through the rice paddies in search of the elusive “third tomb” and learned some very important lessons in planning!

We were joined this week by Jun Kimura from Tokai University in Japan. A long-time partner in the VMAP, Jun is an expert in Asian anchor development and the evolution of shipbuilding technology. He presented two enlightening talks on Asian anchors and the 12 / 13th century wrecks in East Asia and Southeast Asia, and joined the dive teams at the stone anchor site.

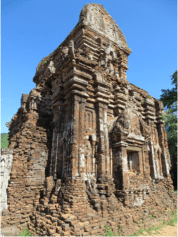

Saturday is our day off and (ever the archaeology nerds) we visited My Son, the ancient Cham religious site, 60kms from Hoi An. Between the 4th and 14th centuries, this valley was the religious center for Champa kings and ruling dynasties, who constructed temples to worship the Hindu god, Shiva. Recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, the temple complex at My Son is widely regarded as being one of the principal historical temple complexes in Southeast Asia, not to mention the paramount heritage site of its kind in Vietnam. Despite being abandoned and engulfed by the forest in the 14th century, then bombed during the American War, the temples that remain have a powerful presence over the landscape.

To round off the week, Sunday was spent in lectures on some of the theory behind underwater cultural heritage management and museology, presented by Mark and Sally. Clyde presented a case study on the management proposal for the World War II wrecks at Subic Bay, Philippines (giving me another reason to return to that part of the world as soon as possible) and the teams caught up on some admin, sleep and pool time. Rested and refreshed (mostly…) we’re ready for week 3!

Follow the project’s Facebook page daily updates from the field! https://www.facebook.com/pages/Vietnam-Maritime-Archeology-Project/308532315956425?fref=ts

Many thanks to everyone for their photos J

- Sophie

![IMG_20141030_105436[1]](https://underwaterheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/img_20141030_1054361.jpg?w=584&h=584)